What is a reliquary?

The idea of conserving the remains of a dead hero goes back to ancient Greece, where relics were displayed along with their swords, shields and even chariots and entire ships.

The Catholic Church adopted the principle with enthusiasm. As soon as a prospective saint breathed their last, their bodies were chopped up into little bits and distributed throughout Christendom where they could be displayed and venerated.

Ornate gilded and bejewelled boxes, known as reliquaries, were constructed to hold these holy relics. Today churches throughout the Catholic world proudly display these magnificent artworks, with their gruesome contents, as objects of veneration and wonder.

Some years ago I visited the monastery of St Gregory in Dubrovnik, which has a large collection of ornate reliquaries. Many of the containers are far grander and larger than the relics they contain: this curious reliquary in the shape of an upturned finger contains a tiny fragment of a bone of St Thomas, barely visible through the small window between the knuckles.

One of the prized possessions in the Dominican monastery of Dubrovnik is the skull of St Dominic, possession of which must be seen as quite a coup for a Dominican monastery in a country he never visited.

Nearby, in an alcove, is displayed a second skull of St Dominic.

I queried this with the curator, who told me that a notable relic was a great asset for a monastery, as it would attract tourists who would bring money and prestige with them.

It was common practice for monks to make raids on each other’s monasteries, in order to secure a particularly notable relic for themselves. If they managed to do so, then it was because the saint wanted to be in their monastery rather than the one from which they stole it.

And if the first monastery happened upon a second skull of the same saint while rummaging in their attic… then it was a miracle, and even more valuable than the one that had been stolen.

And talking of miracles…

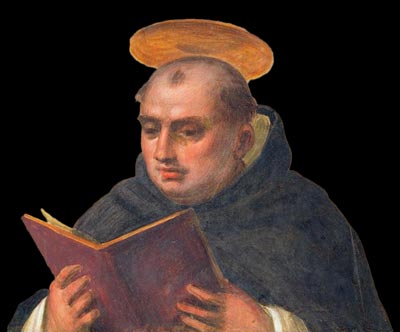

Thomas Aquinas was a noted theologian, best known for his Summa Theologica which contained multiple cast-iron (to him) proofs of the existence of god.

When he died, the Catholic church was keen to canonise him. But there are two main prerequisites for making someone a saint: they either have to have been martyred (undergoing a gruesome death for the church), or they have to have performed a miracle.

Aquinas had led a peaceful, harmonious life, dying comfortably in bed. But when the church looked into whether he had performed any miracles, they came up short. Until they discovered the Miracle of the Herring.

On his deathbed, so the story goes, Aquinas was asked if he needed anything. He replied that he could really fancy a herring, to remind him of his youth.

This posed a problem, as his deathbed was in Italy, where no herrings were to be found. So his attendants gave him a sardine instead.

On eating it, Aquinas pronounced that this was the best herring he had ever tasted. The sardine had turned into a herring in his mouth – and that, faithful followers, was the miracle.